The name ‘cheetah’ is believed to have originated from Sanskrit word chitrak, which means ‘the spotted one’ . The Asiatic cheetah whose long history on the Indian subcontinent gave the Sanskrit-derived vernacular name “cheetah” to the species Acinonyx jubatus, also had a gradual history of habitat loss there. In Punjab, before the thorn forests were cleared and extensively utilized for agriculture and human settlement, they were intermixed with open grasslands grazed by large herds of blackbuck; these coexisted with their main natural predator the Asiatic cheetah . The blackbuck, no longer extant in Punjab, is severely endangered in India. Later, more habitat loss, prey depletion, and trophy hunting were to lead to the extinction of the Asiatic cheetah in other regions of India.

History – How Cheetah Extinct from India ?

Until the 20th century, the Asiatic cheetah was quite common and roamed all across the Middle East, from the Arabian Peninsula to Iran, Afghanistan and India. . In India, they ranged from Jaipur and Lucknow in the north to Mysore in the south, and from Kathiawar in the west to Deogarh in the east .

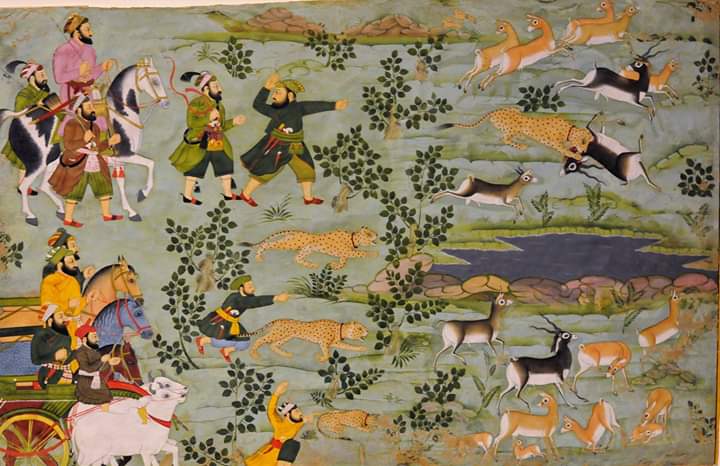

The Asiatic cheetah, also known as the “hunting leopard” in India was kept by kings and princes to hunt gazelle and blackbucks. Firuz Shah Tughluq is considered to be the first ruler in medieval times to tame cheetahs for hunting purposes. The Mughal emperor Akbar had around 1000 Cheetahs for hunting gazelle and blackbucks.

In 1608, a white cheetah was known to be in possession of Raja Vir Singh Deo in Orchha. Mughal king Jahangir describes its spots to be of blue colour in his book Tuzuk-i Jahangiri. This is said to be the only recorded white cheetah. Trapping of large numbers of adult Indian cheetahs, who had already learned hunting skills from wild mothers, for assisting in royal hunts is said to be another major cause of the species rapid decline in India as they never bred in captivity with only one record of a litter ever.

Fewer number of trophy hunting reports at the end of British Rule in India compared to initial years points out to already dwindling population of Cheetahs. A research found at least 230 cheetahs still existed in wild since 1799.

. The Indian reserves were not very thoughtful when creating habitat loss for these oversized cats. The last physical evidence of the Asiatic cheetah in India was thought to be three, all shot by the Maharajah Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Surguja State in 1948, in eastern Madhya Pradesh or northern Chhattisgarh, but a female was sighted in Koriya district, in what is now Chhattisgarh, in 1951.

With the death of the last remaining population of the Asiatic cheetah in India, the species was declared extinct in India; it is the only animal in recorded history to become extinct from India due to unnatural causes. A consequence of the extinction of the cheetahs and subsequently the Indian royalty that prized them was that their grasslands homes came to be controlled, used and managed by local people.

“The grasslands faded and diminished under the hooves of a thousand cattle, they were tilled and ploughed until only a few scattered remnants were preserved in the form of wildlife sanctuaries”

Some Early Efforts for Reintroduction

In the 1970s, the Department of Environment formally wrote to the Iranian government to request Asiatic cheetahs in use for reintroduction and apparently received a positive response. The talks were stalled after the Shah of Iran was deposed in the Iranian Revolution, and the negotiations never progressed.

In August 2009, Jairam Ramesh, the then-Minister of Environment, reportedly rekindled the talks with Iran for sharing a few of their animals. Iran had always been hesitant to commit to the idea, given the very low numbers present in the country. It is said that Iran wanted an Asiatic lion in exchange for a cheetah, and that India was not willing to export any of its lions. The plan to source cheetahs from Iran was eventually dropped in 2010. . The meeting was jointly organised by the WII in association with the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), a prominent NGO based in Delhi. The Cheetah Conservation Fund, IUCN and other NGOs were represented as were high-ranking officials of several State Forest Departments. The meeting also identified Namibia, South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, Tanzania, and the UAE as countries from where the cheetah could be imported to India. “About 5 to 10 animals annually have to be brought to India over a period of 5 to 10 years,” recommended another working group, which was formed for exploring sourcing and translocation of the cheetah.

The Ministry of Environment & Forests approved the recommendation for a detailed survey of potential reintroduction sites in the Indian states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, which were shortlisted during the consultative meeting. Four more Indian states; Tamilnadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra were also considered. The survey would have formed the basis for the roadmap of reintroduction of cheetahs in India, and would have been carried out by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII).

Why Kuno National Park chosen for African Cheetah ?

The vast forest landscape of Kuno Palpur National Park of Madhya Pradesh has become home to eight African cheetahs. With no human settlements, the region is close to the Sal forests of Koriya, now in Chandigarh, where the native Asiatic Cheetah was last spotted almost 70 years ago.

Apart from the high altitudes, coasts, and northeast region, most parts of India are considered a cheetah habitat considering the climatic conditions which are most suited for the wild cats. Thus, several other sites were also considered for the project a decade ago.

Ten sites across Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh were surveyed between 2010 and 2012. Later, Kuno was considered the most suitable place. Based on the assessment carried out by the Wildlife Institute of India and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) depending on climatic variables, prey densities, the population of competing predators, and the historical range, Kuno was considered to be the most preferred habitat.

Besides, high population density and depleting open grasslands pose a threat to animals in India. Kuno is one of the few wildlife sites in the country where there has been a complete relocation of around 24 villages, and their domesticated livestock from inside the park years ago. The village sites and their agricultural fields have been covered by grasses and are managed by savannah habitats.

Kuno is the home of four large felines in India namely – tiger, lion, leopard, and cheetah. The government’s plan ensured that the animals coexist as they did in the past. Though the only surviving population of lions is in Gujarat, Kuno was initially proposed to provide a second home.

The forest bears the significant number of leopards per 100 square kilometres. However, this remains a concern, taking into account, that the much-stronger leopard has an advantage over the slender cheetah whose strength mainly lies in its fast speed. Besides, they are assumed to be more adaptive potential and wilder animals than the cheetah.

Both are known to coexist in the wild if there is an adequate prey base and other resources. According to the authorities, prey restoration, reintroduction of lions, and colonisation of tigers in the future are both viable possibilities in the Kuno landscape.

An estimate by the government data states that the national park can be home to at least 21 cheetahs at present and if necessary efforts are taken and prey base is maintained, it can even hold as many as 36 cheetahs.

If the current translocation becomes successful, a plan will be made to establish a meta-population of cheetahs at Kuno and work towards translocating the wild cats to other selected locations.